This post first appeared on the blog of Biophysical Society. This was the third blog post in a 3-part series of blogs that I wrote about my favorite Biophysical Journal papers of 2019. You can read parts 1 and 2, here and here.

A new way of trapping bacteria

Araujo, G., Chen, W., Mani, S., & Tang, J. X. (2019). Orbiting of Flagellated Bacteria within a Thin Fluid Film around Micrometer-Sized Particles. Biophysical Journal, 117(2), 346-354.

link to article

The field of biophysics owes its existence to the fact that the principles and approaches of physical sciences have been incredibly successful at elucidating biological phenomena. The reason behind this success is quite simple. At one level or another, most if not all biological processes can be broken down into physical interactions between two or more interacting partners. Once such interactions are identified, it can then often be straightforward to describe them using well-established physical laws.

A shining example of how to effectively marry physics and biology is found in the field of bacterial motility. Many bacteria swim through fluids by rotating rigid helical filaments driven by a sophisticated molecular nanomachine called the flagellar motor. Over the years, the study of flagella-driven bacterial motility has gained tremendously from using the tools of physics to attack this problem. Great progress has been made by combining careful experiments to observe bacterial motility with the application of hydrodynamics to rationalize the observations.

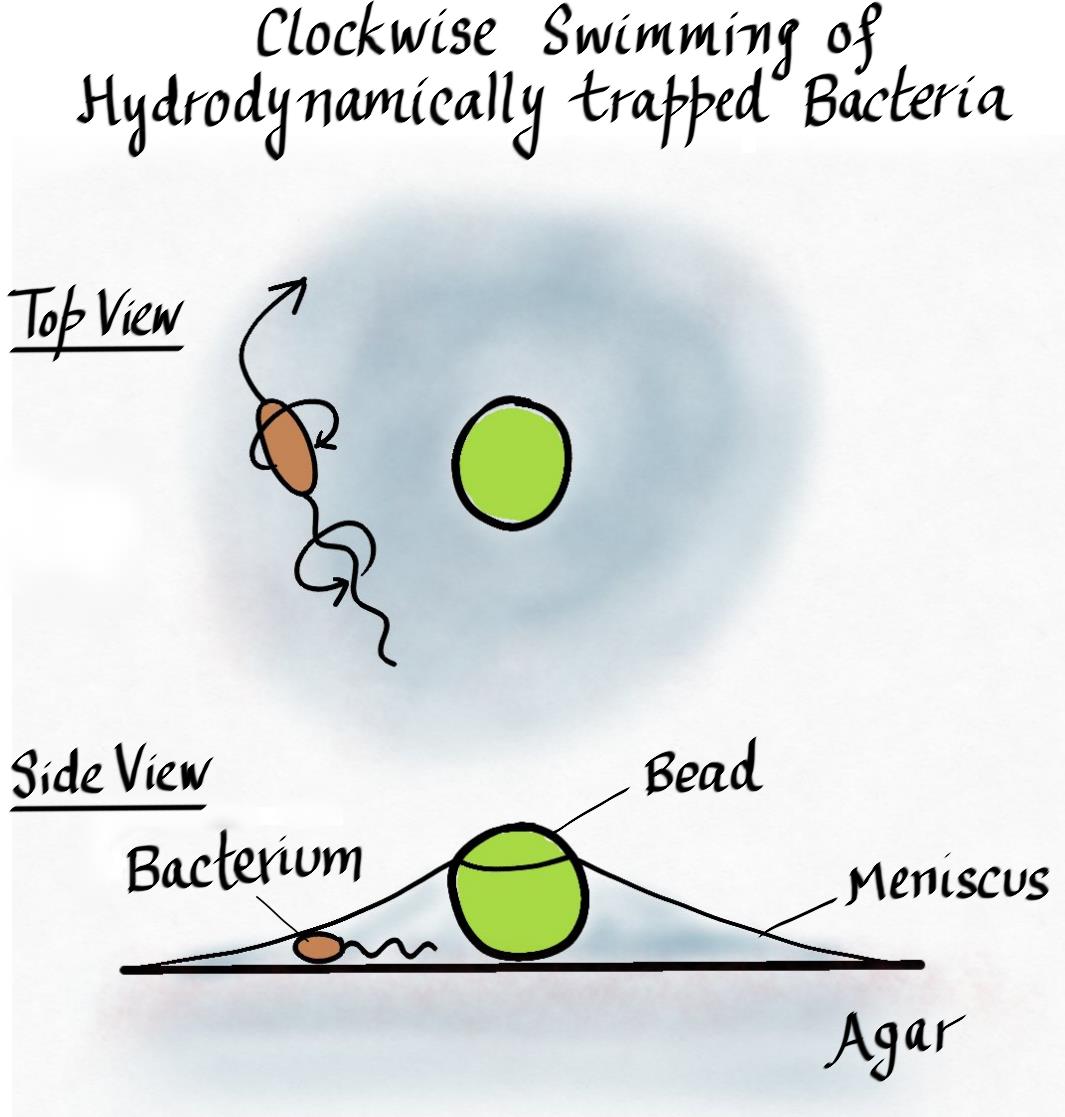

A recent study published in Biophysical Journal carries on this rich tradition. Araujo and colleagues reported a novel observation of trapping bacteria in thin liquid films. They grew a swarm of motile bacteria on top of an agar plate and dropped a suspension of micron-sized particles at the edge of the swarm. Within minutes, most of the liquid dropped by the researchers evaporated, leaving behind the deposited particles and small tents of fluid around them where surface tension pulled the meniscus away from the agar surface. When the researchers looked closer, they found bacteria trapped and swimming around in this tent. The most striking observation was that when viewed from above the meniscus, all the trapped bacteria were swimming in circles going clockwise!

An observation like that would get any scientist excited and eager to learn more. Why were the bacteria trapped? Why did they swim only clockwise? How long will they remain trapped if left untouched? Through a series of exploratory experiments, the researchers have revealed a rather peculiar situation in which the interplay between surface tension, evaporation, and the hydrodynamics of flagella-driven bacterial motility lead to the bacteria getting trapped and swimming in circles.

The fluid tent was formed because at the minute size scales relevant here, surface tension is the dominant fluid force around. This is why small insects can easily “walk” on water, because the force required to break through the water surface is much larger than what gravity can apply on such small organisms. Similarly, the surface tension at the fluid-solid interface between a micron-sized particle and the surrounding medium causes the meniscus to rise against gravity. Accordingly, when the researchers placed small particles on the agar surface, fluid was pulled away from the agar and small fluid-filled tents were formed, trapping bacteria within the bounds where the meniscus met the agar surface.

Thanks to another very useful principle of physics, such fluid tents were stable for hours at a time. Evaporation would normally deplete such a small volume of fluid within seconds. However, since the tent rested on top of a large reservoir of fluid (the agar gel), any loss of fluid to evaporation was supplanted by an inflow from the agar through wicking action. Surface tension for the win, again!

Why do the trapped bacteria swim clockwise when viewed from above? This is where the hydrodynamics of flagella driven motility kicks in. As mentioned before, many bacteria swim by rotating helical rigid filaments through the fluid. For bacteria such as Escherichia coli (one of the species studies by Araujo et al.), the flagellar filaments are left-handed helices. The cell swims forward by rotating the flagella counterclockwise (viewed from outside the cell), while the cell body counter-rotates clockwise to balance the torque. When the cell swims near the agar surface, the side closer to the agar experiences higher viscous drag. As a result, along with moving forward, the cell effectively rolls on its side, resulting in circular trajectories. For clockwise rotating cell bodies, this results in clockwise swimming when viewed from above.

There we have it. Grow some swarming bacteria on an agar plate and throw in some micron-sized particles, and you too can build your own bacterial traps. What you do with the bacteria you trap is up to you. Maybe you trap bacteria with other exotic modes of swimming. Maybe you play with the agar concentration to make it more or less stiff. You could even turn the agar plate upside down to give some extra challenge to surface tension. The possibilities are endless. As we have seen in the case of the Araujo et al. study, you can learn a lot by just observing.